Reproduction and population growth – how many foals?

The number of foals when compared to the number of other horses or total population is a useful measure of a population’s reproduction because it is so easily obtained and interpreted. It is also an indication of a population’s potential to grow because it cannot grow faster than it produces foals.

The ratio of foals to other horses, or percentage of foals in the population, is a powerful measure of reproduction because foals are easily distinguished from other horses during population estimates, it does not require that other horses be aged and sexed, and is an indication of the populations potential to grow. Photo source: http://www.reviewjournal.com.

Easy to get

Foals are quickly and reliably distinguished from other horses, even from a light plane or helicopter and especially if the population estimate is made soon after the end of the foaling season. Late-summer through early autumn would be the ideal time for most populations. Most foals are born late-spring and rarely in late-autumn and winter.

Importantly, the measurement does not require that other horses in the population are aged or sexed. More studies, even more detailed demographic studies, should present a ratio of foals to other horses to help make comparisons amongst populations.

Easy to interpret

Conveniently, the proportion of foals in the population (number of foals divided total population size) will be larger than a population’s instantaneous rate of increase – given the label r by population biologists – because there must also be deaths.

For the same reason, the ratio of foals to other horses (number of foals divided by the number of other horses) should be larger than a population’s growth in the same year – that is given the label lambda, λ.

A check for growth potential

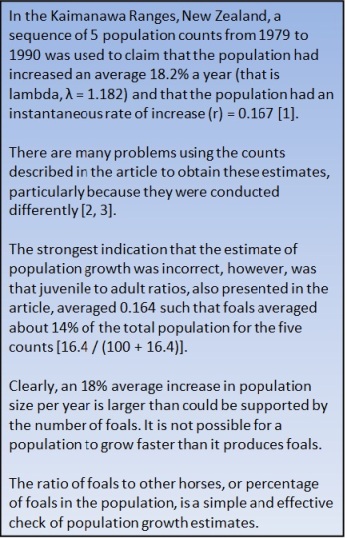

Because the proportion of population that are foals and ratio  of foals to other horses should be larger than r and λ, respectively, they are a useful guide of a populations potential to grow or a useful retrospective check of the reliability of population growth estimates.

of foals to other horses should be larger than r and λ, respectively, they are a useful guide of a populations potential to grow or a useful retrospective check of the reliability of population growth estimates.

There are some egregious examples published in the scientific literature where extraordinary claims of feral horse population growth were larger than the foals in the population could support (see insert). When an estimate of population size is made, I recommend that a separate count of foals also be made to validate subsequent estimates of population growth.

Bibliography

Reblogged this on EQUILIBRE Gaiá and commented:

In this new blog from Wayne Linklater, he takes the reader through the feasibility of using the number of foals in a given population to estimate its potential growth. After all, as Wayne points out: a population can not grow faster than it produces foals.

Also the average number of foal deaths per season should also taken into account otherwise the estimated population growth is skewed higher than reality. Foal deaths affect the estimated population growth as not all foals born live to reach breeding age.

Absolutely – we will consider death rates as we work our way thought the demography of horses from mare reproduction to survival rates of different age-sex classes.

Thank you for your comment!

Pingback: Populations’ reproductive rates compared – how high, how variable? | Perissodactyla

Pingback: Two-year-olds can foal too – but it is uncommon | Perissodactyla

Pingback: Teenage pregnancy in horses… | Perissodactyla

I realize I’m terribly late to the party, but…

Some associates and I worked on a report a few months back regarding the foal to yearling survival rate in four groups of Western wild horses that had been removed by the BLM.

The animals were removed from four separate areas; two sets occurred in Winter, 2009-10 and Summer, 2010, the others Summer and late Fall 2011.

Our data found that the foals captured did indeed average about 20% for those years, but the yearlings accounted for a population increase of only about 10%.

The first year of a young wild horse’s life is riddled with risks, from predators to accidents. Most data sets simply assume every birth will inevitably result in a successful adulthood.

BLM bases it’s population counts on the possible foal crop for a particular year, and relies heavily on estimates rather than observation. Also absent, unfortunately, is any acknowledgement of mortality. It’s hard to consider seriously any population data that omits the actuality of death across any age groups on the ranges; that, too, could be based on ‘estimate’.

Below is a link to our research paper:

https://app.box.com/s/n4anbas6y43ugb1rr5sk

It is simplistic, and short on variables; it’s my hope we’ll be able to make a more thorough and finer-detailed assessment in the near future.

Thank you Lisa for your comment and the research paper. I agree, mortality of older foals can have a significant impact. The numbers of foals can be a poor indicator of population growth where there is significant mortality. Foal mortality is also likely to vary considerably between years and sites and so several years of data are necessary to obtain a representative sample of typical recruitment. Numbers of yearlings would be a better indicator of population growth potential but, unfortunately, they are more difficult to distinguish from other age classes at distance, in the same way that foals can be, and so most population assessments report foals. More detailed age-class data like yours are required – Regards, Wayne.